At Gaumont

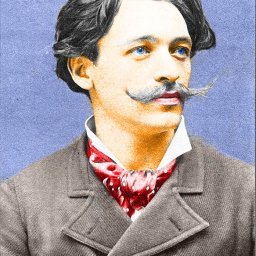

By 1907, at the age of 50 Émile Cohl, became a part of the new sensation motion pictures. How he actually entered the business is vague and uncertain. According to Jean-Georges Auriol in a book of 1930, one day Cohl was walking down the street when he spotted a poster advertising a movie obviously stolen from one of his strips. Outraged, he confronted the manager of the offending studio “Gaumont” and was hired on the spot as a scenarist, responsible for one-page story ideas for movies. The story doesn’t give the details of which strip and which short film; it is also possible that the story is completely false, and that Cohl was approached for the job, either by director Etienne Arnaud or by artistic director Louis Feuillade, both of whom had once worked for caricature papers and therefore could have known about Cohl.

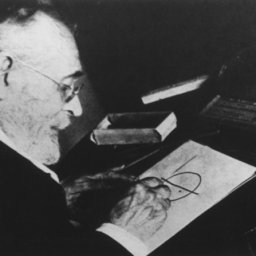

At Gaumont, Cohl collaborated with the other directors, learning cinematography and direction. But his specialty was animation. He worked in a corner of the studio with a vertically-mounted Gaumont camera and a single assistant to operate it. He turned out four sequences a month for insertion in mostly-live action films. Studio director Léon Gaumont, in one of his visits, dubbed him “the Benedictine”.

The idea for doing animation was born from the huge success of J. Stuart Blackton’s “The Haunted Hotel“, released by Vitagraph, premiered in Paris in April 1907 and was huge success. Immediately there was a demand for more films using its incredible object animation techniques. According to a story told by Arnaud in 1922, Gaumont had ordered his staff to figure out the “mystery of ‘The Haunted Hotel’.” When nobody could figure out the technique, Cohl studied the film frame by frame, and in this way discovered it. Cohl never corroborated this story. Also, there were many films released before 1907 with stop-motion and/or drawn animation in them, which could have taught Cohl animation. But given the intellectual genius of Cohl, it is hard to imagine that he didn’t just work the technique out on his own.

Cohl made “Fantasmagorie” from February to May or June 1908. This is considered the first fully animated film ever made. It was made up of 700 drawings, each of which was double-exposed, Despite the short running time of about two minutes, the piece was packed with material devised in a “stream of consciousness” style. It was done using a “chalk-line effect” in which black lines are filmed on white paper, then reversing the negative to make it look like white chalk on a black chalkboard. The film, in all of its wild transformations, is a direct tribute to the by-then forgotten Incoherent movement. The title is a reference to the “fantasmograph“, a mid-Nineteenth Century variant of the magic lantern that projected ghostly images that floated across the walls.

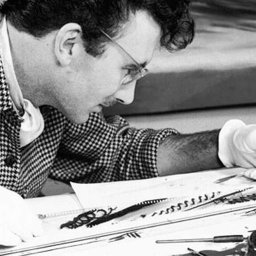

“Fantasmagorie” was released on August 17, 1908. This was followed by two more films, “Le Cauchemar du fantoche” (“The Puppet’s Nightmare”) and “Un Drame chez les fantoches” (“A Puppet Drama“, called “The Love Affair in Toyland” for American release and “Mystical Love-Making” for British release), all completed in 1908. These three films are united by their chalk-line style, the stick-figure clown protagonists, and the constant transformations. Cohl made the plots of these films up as he was filming them. He would put a drawing on the lightbox, photograph it, trace onto next sheet with slight changes, photograph that, and so on. This meant that the pictures did not jitter and the plot was spontaneous. Cohl had to calculate the timing in advance. The process was very time-consuming and demanding. Probably therefore he moved away from drawn animation after “Un Drame chez les fantoches“.

Playlist of Emile Cohl’s Movies Made at Gaumont

The rest of the films Cohl made for Gaumont involve strange transformations as in “Les Joyeaux Microbes” (1909) (“The Joyous Microbes“, aka “The Merry Microbes” (UK)), some great matte effects as in “Clair de lune espagnol” (1909) (“Spanish Moonlight“, aka “The Man in the Moon” (US), aka “The Moon-Struck Matador” (UK)), and loving puppet animation as in “Le Tout Petit Faust” (1910) (“The Little Faust“, aka “The Beautiful Margaret” (US)), and “Mobilier fidèle” (1910), released in the U.S. as “The Automatic Moving Company” in 1912. Other films used jointed cut-outs or animated matches which later became Cohl’s favourite.

In his lifetime, Cohl’s most-famous film was “Le Peintre néo-impressionniste” (“The Neo-Impressionistic Painter” last in the above playlist), made in 1910. An artist is sketching a classically-draped model holding a broom as a stick-figure when a collector storms in demanding to know the progress of his work. The artist shows the collector a series of blank colored canvases (the film was partially colour tinted for this). As he gives their ridiculous titles, the collector imagines them being drawn on the canvas. The collector is soon so delirious that he buys every blank canvas he can see. Quite obviously, the artist is not a neo-Impressionist –he’s an Incoherent.

The Cohl animated films had a large impact through their American distribution by Kleine. Many of them received rave reviews in the trade magazines, although Cohl was only identified as “Gaumont’s animator“. Traces and inspiration of Cohl’s work can be seen in many films of the other animators like Winsor McCay. Motifs of Cohl’s can be found in “Little Nemo” and later films by McCay: the dots coalescing into Little Nemo reflect effects in “Un Drame chez les fantoches” and “Les Joyeaux Microbes“; the metamorphosis of the rose into the Princess may have been inspired by “Fantasmagorie“; the titular character of “The Story of a Mosquito” (1912) sharpening his beak comes from “Un Drame chez les fantoches”.