Norman McLaren (April 11, 1914 – January 27, 1987) was a pioneer in both animation and filmmaking. He devoted his life to experiment and innovation in animation. For him, movement was central to the art of cinema and he spent most of his time exploring the different ways of creating movement on film.

Although he never made a feature film or worked in the commercial sector, McLaren was one of the most influential animators of the 20th century. He is renowned as one of greatest geniuses in animation; best known for his films which he developed new animation techniques such as drawing and/or scratching directly on film stock and Pixilation. He was forever adapting or inventing new techniques of animation. For Beyond Dull Care (1949) and Blinkity Blank (1955) he drew or painted directly onto film, and in his Oscar-winning anti-war film Neighbours (1952) he used the frame-by-frame photographic technique of pixillation to animate living people. He used cut-out shapes for films such as Alouette (1944), Rythmetic (1956) and La Merle (1958), his film Pas de Deux (1967) used a technique that combined stroboscopic flash shots with multiple printing. McLaren was also drawn to abstraction with films such as Lines Vertical (1960) and Lines Horizontal (1961). His films often explored the relationship between music and movement, and he even drew directly onto film to produce sound tracks.

His constant experimentation and technical virtuosity brought McLaren many admirers, particularly amongst animators, and his work still has a radical edge, showing that animation has no boundaries. This article talks about his experimentations with various techniques of animation.

McLaren was an avid moviegoer, but it was the Russian films of Eisenstein and Pudovkin that cinema took a new place for him in the cultural hierarchy in the year 1934. He found it a great medium. He was very excited by what what one can do with it. He felt that painting was an art of the past and movie making was The Art of today. In the same year, McLaren saw german animator Oscar Fischinger’s abstract film, which was also a revelation for him. McLaren used to see abstractions in his mind as he listened to music. With film, he realized he could make these abstractions visible.

His mind was made up and he joined a newly formed filmmaking club at the art school where he displayed an original and energetic talent which. His student films were mainly live-action; he was fascinated by the movie camera and sought to exploit it to its maximum. His films were Seven Till Five, a documentation of the day’s activities at the art school; Camera Makes Whoopee, an account of the preparation for, and the actual annual student ball; Hell Unlimited, an anti-war film, a melange of live action and drawn and object animation. These films were shot with a very simple 16 mm camera and lost of short shots and close-ups were used.

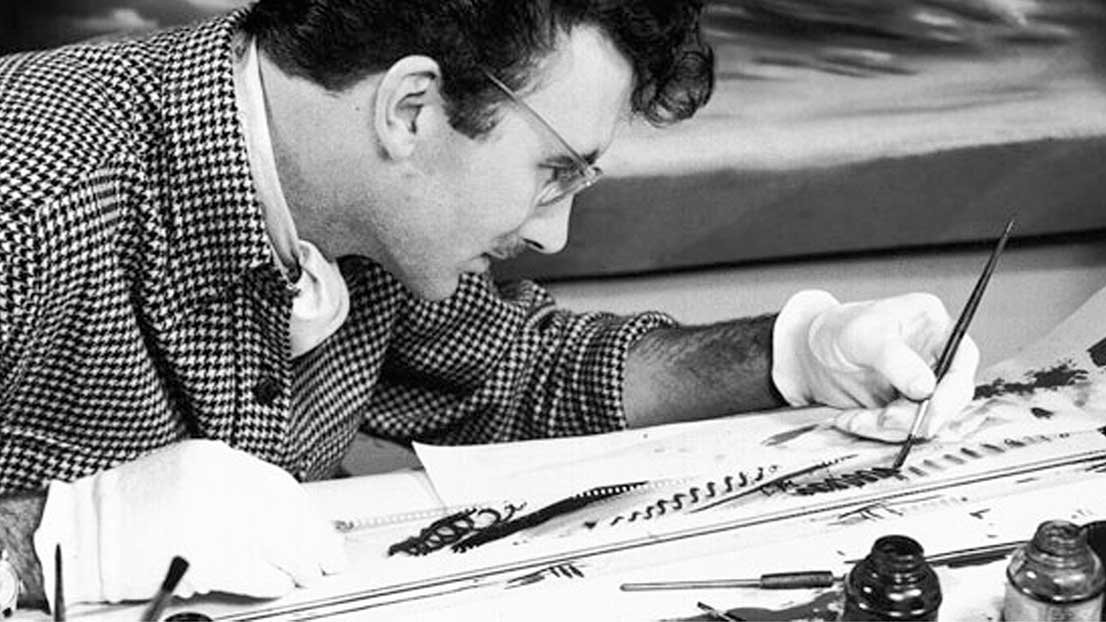

Hand Painted Abstraction (1933) was a silent abstract film, designed to be accompanied by discs of any fast jazz or popular music. These days a movie camera was extremely difficult to afford. So, McLaren hand-painted on salvaged 35 mm film with a very limited range of semi-transparent dyes, shoe-polish (can you imagine?) and India ink, and with total disregard for the frame-line or for synchronization with the music. The very rapid fluctuations of patterns and the very fast music created an acceptable random synchronization, which often looked very intentional.

McLaren then worked for John Grierson at the General Post Office Unit from the autumn of 1936 until 1939 where he made documentaries. One of the significant films he made there, Love on the Wing, is a movie with continually metamorphosing linear images and symbols were drawn with an ordinary pen and India ink on clear 35 mm film stock. A positive and a negative (black-line-on-clear) was made to protect the original. Painted colour multiplane traveling backgrounds were shot on Dufay-colour negative. The black-line-on-clear negative, when printed bi-pack with the Dufay colour negative, gave a clean-line image on positive colour background. This acted as the master positive from which a colour dupe-negative and all release prints were made.

Playlist of Dots, Loops, Scherzo, Boogie Doodle

After immigrating to the new York, USA. Here Baroness Von Rebay, subsidized the making of some of these films – Dots, Loops, Scherzo, Stars and Stripes and Boogie Doodle. They were drawn directly on clear 35 mm film with pen and India ink. This produced a black-line image original (first generation). From this a clear-line-image-on-black print (second generation) was made, and then from it a black-line-image-on-clear print (third generation) was made. The second and third generation prints were used to make colour prints on a now defunct 2-colour black & white separation process (Warner Colour System). This process used two dyes, red and blue; two passes were needed to make the final colour print. Printing the second generation print (clear image on black ground) with the red dye produced a red linear image on a clear ground. Then, with a second pass, using the third generation print (black-image-on-clear) printing for the blue dye produced a blue background with an unexposed linear image. The final result was a red linear image on a blue ground.

The sound was also hand-drawn over a range of three octaves by drawing with pen or brush and ink on clear film for Dots and Loops and by engraving or scratching black, or opaque coloured leader with knife, needle or stylus in Scherzo, Stars and Stripes and Boogie Doodle. He had discovered this method by accident while working at GPO and he called this as Animated Sound.